I became a filmmaker in 2009, after recording the last conversation I had with my mother before her death. Film seemed to be the only vehicle that could carry the narrative of my mother’s service during World War II. So, I embarked on a year-and-a-half-long journey to make, what turned out to be, an 8-minute documentary.

SPAR portrait of the author’s mother.

It was tough at first. I was still working full time, still grieving. In preparation, I spent a lot of spare time watching documentaries to see which personal stories affected me, trying to analyze them from the viewpoint of a critic. Who was the film intended for? Which voice would carry the narrative? What resolution was I hoping for in my own film, and what good (or harm) could come out of airing sensitive material? Here is a synopsis of what I learned in the process of answering these questions.

Research and establish the film’s purpose

When I began, I knew little about my mother’s service; the general public was also unfamiliar with her Coast Guard Women’s Auxilliary called the SPARs (from the acronym for the Coast Guard’s motto, Semper Paratus, Always Ready). Even the Coast Guard Archivist I interviewed early in my research had very few resources about the SPARs, and WWII museums dealt with information on this branch of Women’s Auxiliary largely as a footnote.

In our last conversation, I learned that my mother was one of the first 12 recruits (out of over 10,000 women who eventually enlisted). She was also told she could not be considered for Navy officer candidate school because she was Jewish. I started envisioning the film as an educational tool and a piece of women’s military history.

I story-boarded and edited my mother’s voice to fit not-yet-realized-footage and even dreamed at night what the film would look like as I worked through each scene.

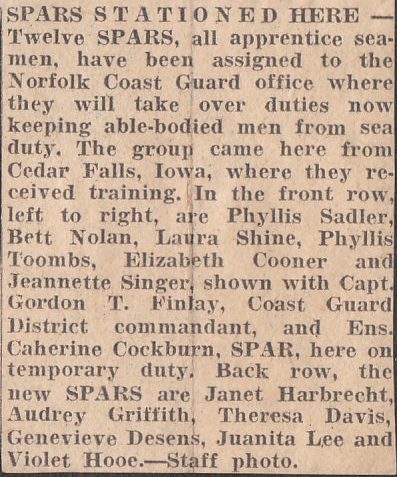

News article naming recruits.

Eventually, I found a news article with the names of all 12 first recruits. Then I connected with some of the sons and daughters of the eleven other women who served with my mother in that first class, along with war experts and military personnel throughout the country.

I wanted my mother’s story to be verifiable. Since she was already in her 90s, I didn’t want to chance that my mother’s memories were embellished or her own imaginations.

Also, it was imperative that any film sequences stayed true to the 1940s, including the train used in the film to depict the 12’s journey from training in Iowa to their duty base in Virginia. Even something as small as this can be an extremely crucial detail in a documentary film. As an interesting side-note, their train got left on a side track for a day and a half with the 12 women on board, in error.

Bring objectivity into the project

I collaborated with a film editor who was willing to work with me on a super-low-budget film (with no outside funding) to ensure that I stayed focused. It was a great partnership. Ray was devoid of the emotional baggage I carried and was willing to challenge me on anything that took the film away from its intended point of view.

A still image from the train section of the film.

This was one of the best decisions I could have made. Having people on your team who are invested, but not emotionally connected, can bring objectivity to your very personal story.

Together you can ask: Is this relevant? Is each frame carrying the action? Does it help maintain the integrity of the message?

Evaluate the product

During the making of the film, I periodically showed clips to gauge peoples’ reactions, making adjustments as needed. Picking reviewers carefully is an essential ingredient here (akin to having friends who aren’t afraid to tell you the truth, even when you look a mess).

A proliferation of searing documentaries have come out in recent years centered around a wide variety of personal family stories. Not all subjects and approaches may appeal to a general audience. Sometimes heavy editing is needed to avoid driving home a point too emphatically, or making the audience feel trapped by what the film wants them to experience emotionally.

Revise and cut to the essentials

The SPARS 12 with author’s mother at far right.

Even the shortest films can benefit from increased scrutiny and paring down. Be very clear about your goals and objectives for making the film, ensuring that each frame carries the intended purpose forward. In the creative writing classes I teach, I subscribe to the credo of leave them wanting more rather than less, and in showing, not telling. This is what film can do so well, one carefully-crafted visual scene replacing pages of dialogue or narration. It is tough to remove scenes from your project (what is often referred to as ‘killing your darlings’), but it is essential to evaluate, to revise, and to cut.

Each filmmaker undoubtedly has their own formula when taking on a personal project regarding how to step back and view their film through open eyes. To me this entails a heavy emphasis on planning and evaluation, revision and reevaluation—breaking out of the artistic tendency to work in a vacuum. Then comes the thrill of sitting in the back of a theatre to watch the audience as they view your film that first night on the big screen.

Watch Marilyn’s film here.