The Fund for Investigative Journalism (FIJ) was founded in 1969 to support independent investigative reporters around the world through research grants. FIJ uses Submittable to administer this program and we recently spoke with the current FIJ Board President Ricardo Sandoval-Palos.

Tell me about the Fund for Investigative Journalism and how it has evolved.

The fund is 40 years old — it has a long rich history, taking us back to one of the first reporting grants, issued to Seymour Hersh. The grant financed research that allowed him to break the story of the My Lai Massacre.

Since its start, the fund has operated to directly support journalists. Investigative reporters and journalists tend to be like a communal neighborhood where a lot of us know each other; we’ve worked together, we’ve collaborated, we’ve competed, we’ve helped each other at times. FIJ did this community quite a service for many years.

Photo of Seymour Hersh. Image sourced here.

However, what happened in the last two decades was a shrinking of the kind of investigative reporting attached to traditional news operations, and newspapers in particular. One of the easiest ways to save money was to eliminate investigative teams. At the same time, as traditional newsrooms shrank, the community of freelance reporters started to grow.

The freelance community is the one community still expanding by leaps and bounds in this industry. Unfortunately, it’s also the least supported and the poorest paid. We saw that there was a need to help independent investigative reporters continue to do the work that makes us proud and has an impact for society.

A recent goal has been to explore giving slightly fewer grants, but giving more per grant, to increase the quality of the stories that we support. This is not to say that we will not, and have not, put money behind very successful stories – and we will continue to do this. For example, we’ve given money in $2000 and $3000 increments to different reporters working on good projects but sometimes the projects are short term or don’t have, perhaps, the level of impact that we’d like them to have. To that end, during this past round of grants we actually hit a bit of a record by awarding $120,000 in grants, just in one cycle.

How do you assess the impact of FIJ grants?

Well, there is a traditional way of measuring the impact, right? Like someone won the Pulitzer: that’s a big impact – it makes us feel good about ourselves as journalists. But what I think we’re after is really defined by the stories that create change, that have people talking about changing things as a result and questioning governments, institutions, and practices that have been highlighted in the story.

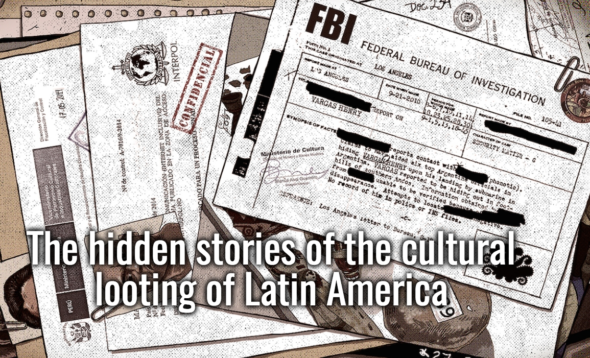

From David Hidalgo’s FIJ-supported piece on stolen artifacts. Image source here.

We’ve supported stories about asset forfeiture that have had a positive result. We underwrote a story last year for a journalist who found that the government of Puerto Rico was sending recovering addicts to Chicago who were then becoming homeless. We underwrote a story out of Peru that identified profiteers that were trafficking artifacts and taking them away from indigenous peoples; that story was recently named one of the best investigative stories in Latin America.

It’s those kinds of stories that shine a sharp light on injustice, or practices by governments and institutions, that need to be the put out into the public sector so something can be done. That’s the kind of impact I want to see.

What are the biggest challenges for freelance journalists in this current administration, and how can we support them?

The major issue supersedes the current administration — I think the fundamental problem with the investigative reporting, and in particular independent investigative reporting, is funding.

Reporters who do it on their own are often working on a shoestring budget. There’s an interesting survey of independent investigative reporters that was done by a new group called FIRE. They found that a good percentage of independent investigative reporters support themselves by sometimes borrowing money to make sure that they can get their stories completed.

This is a terrible situation. With the rates that magazines and other publications pay now, it’s not sustainable for a freelancer, let alone for an investigative freelancer with a lot more in the way of cost for necessary research and data, or having to pay for reams of documents that they might be getting from a Freedom of Information Act request. Let alone thinking about things like libel insurance. These writers have to piece together support from organizations like ours and any number of other grant making foundations, then continue to do it.

Given the climate of distrust around major news outlets right now, I wonder if freelancers have a unique opportunity.

I think there’s a general distrust of all journalists and it’s unfortunate because it’s one of those things that has been fed by ideology, and fed by selfish want, and need, on the part of politicians. What you can do to pump up your own reputation these days as a politician is to badmouth the people who are bringing the you the news.

That’s how fake news can work. When you can build up distrust in the traditional media, then it’s easier to inject what you, as the thought leader in your particular community, label as the real truth. What happens then — because of the Internet, because of this ability to create your own bubble and live within that bubble — is you get to the point where you don’t have to read about anybody else. You can go through life and not have to pay attention to the other guy anymore because you have your Internet community, you have your far-flung neighborhood of people who think just like you. That’s not healthy for society.

Because of this, all journalists have to meet a higher bar now. We have a tougher task. We have a responsibility to make our process as transparent as possible, so we can then show readers that it’s not fake news. By being transparent with our process, by being transparent with our sources and being transparent with the way we work as journalists, I think we defend ourselves and defend our position as the purveyors of responsible stories. It’s really important to support the investigative reporters who are doing that kind of work.

I don’t think a lot of people know how their news is made, so transparency seem really valuable for everybody.

I think it’s really critical. I was trained as a journalist not to rely on anonymous sources, if at all possible. And if you do need an anonymous source, there has to be a very good reason for that person to remain anonymous. You have to make those policies known, and explain why there are anonymous sources in the story, so the readers can get an idea of what your process is like.

In his day job, Ricardo serves as managing editor for 100Reporters.

For example, my daytime job is editing investigative projects that come to me from around the globe. Each story has to come with a fact-checking file. I need to see the primary sources that the reporter used to generate each statement, paragraph, or finding. If the reporter can’t do this, then I have a problem. All of our stories are then subsequently read by a lawyer to make sure that our process has adhered to the highest ethical standards for investigative reporting.

I think at the end of the day — I know it’s a cliché — the truth will out. What I have is a set of facts that I could use to challenge another person’s set of facts so I can say: Here’s how I did it. How did you do it?

Do you have any advice for young people getting started in journalism, or investigative journalism?

Write. Just write. Write what you know, and if you don’t know something dedicate yourself to studying it and then write stories about it, because the more you write about something, the more you know about it.

These days, I’m convinced that the old model of getting into journalism — working at a tiny newspaper and then working your way up to The New York Times — that ladder doesn’t exist anymore. So, the more you can do to expand your abilities is important. Get into broadcast. Learn how to edit and record radio, audio and video so you’re really expanding your toolkit. Those are the journalists of the future, the people who can comfortably move from one platform to another.

And then once you establish yourself, if you want to become an investigative reporter, be aggressive about asking why and how. The more you ask of those kinds of contextual questions, the why and how, the more you’re going to find yourself investigating.

What made you want to become a journalist?

Journalism is all I’ve done since I was 12 years old. The thing that has always driven me is a sense of helping right wrongs, the desire to identify what the community thinks might be wrong with government and institutions, and then ask questions: Why is it that way? What can be done about it?

It’s been curiosity, but curiosity driven by a sense of fair play.

**

Ricardo Sandoval-Palos is the managing editor for 100Reporters and the current President of the FIJ Board. Previously, he was an editor for National Public Radio, senior researcher for Human Rights Watch and an editor at the Center for Public Integrity. Before that he was assistant city editor and weekend city editor at the Sacramento Bee, where his reporters covered health, transportation and environmental issues. Sandoval Palos also was a Latin America correspondent, based in Mexico City, for the Dallas Morning News and Knight Ridder Newspapers. He has written extensively about drug trafficking and investigated the serial murders of women in Ciudad Juarez. Sandoval Palos’ career has spanned three decades and includes award-winning coverage of the savings and loan scandal and the deregulation of public utility companies. His list of awards includes the Overseas Press Club and the Inter-American Press Association, for “Lost in Transit,” a probe of profiteering in the international remittance business, and the Gerald Loeb prize for business journalism. He co-authored of the biography “The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement” published by Harcourt. He was born in Mexico and raised in San Diego, California