Free Verse is a non-profit dedicated to serving incarcerated youth through creative writing. They are based in Missoula, MT, where Submittable is located. I was lucky to spend a snowy night last week with Sarah Kahn, Director and founder of Free Verse, and Submittable Product Manager Bracha Tenenbaum, a teacher for the organization.

Free Verse is a non-profit dedicated to serving incarcerated youth through creative writing. They are based in Missoula, MT, where Submittable is located. I was lucky to spend a snowy night last week with Sarah Kahn, Director and founder of Free Verse, and Submittable Product Manager Bracha Tenenbaum, a teacher for the organization.

How did Free Verse begin? Bracha, how did you get involved?

Sarah: When I moved to Montana for graduate school, I knew I wanted to volunteer at a juvenile detention center, but I couldn’t find a volunteer organization doing that. It took me almost five months to get into the juvenile hall in Missoula. I basically stalked the director at the time, who was very nice but didn’t know what I wanted from him. I started Free Verse with a few of my writer friends. At first, it was just four of us, figuring it out as we went. Over time, we grew, started going every week, all year, got to know the kids, built a relationship with the hall, started visiting new halls across the state.

Bracha: I was interested in helping underserved kids write their college admittance essays and started asking around for ways to get involved. When I heard about Free Verse, I thought, whoa, I want to be doing that.

What is this teaching environment like? Any particular challenges?

Sarah: We go in twice a week and the same kids see the same teachers, usually for about an hour.Some of the kids we see every week and some are new and never come back. We typically serve anywhere from 2-7 students and we currently have six teachers (plus me): Lisbet Portman, Lexi Fredericks, Anna Zumbahlen, Jules Ohman, Taylor White, and Bracha.

It requires being creative–1 out of 20 times we get to do the lesson we planned. Sometimes you walk in and there’s two kids who were just sentenced and don’t want to talk about Junot Diaz. We’re not there to force them to do something they don’t want to do. What’s the point in that.

Bracha: These are wise kids with lots of life experience. It’s rare that you teach what you plan to teach.

Free Verse Instructors Bracha Tenenbaum and Brittani Hissom outside Pine Hills Youth Correctional.

Sarah: I brought a lesson recently that was meant for seven kids, and there were only two girls in class that day. They were not having it. I was training some teachers, so we just read the piece to them–it was a lesson on code switching. We ended up just having them write these mini-dictionaries of slang, phrases they’d made up with their friends. It was cool because they could teach us something. We try not to keep the power dynamic one-sided. We hate being just one more group of people telling them what to do.

Bracha: We usually bring in a published piece, or excerpt, to read and discuss. I like to use contemporary authors like Rachel Harper, Shulem Deen, and Brian Stevenson. Then the students have about ten minutes of writing time. After writing, they can share what they wrote if they want to but there’s no pressure. What they share can be really emotional. Many times the kids who try to come off as the toughest will be the ones holding back tears when they read their work out loud.

What have been the most surprising things about working in/for this organization and with youth writers?

Bracha: Society has this idea of what it means to be in prison that has to do with fear, that someone incarcerated is someone to be scared of. When you get to know these kids, you realize they’re in there because of circumstances, and their circumstances are completely out of their control. They’re kids and as kids they have no control over the home they return to at night or the neighborhood they play in during the day.

One student told me, “I’ll be back here in a week.” When I asked him why, he said, “I don’t know anyone who’s sober.” He must have been 15 or 16 years old. That student explained that to stay sober and out of prison, he had to completely remove himself from his friend group–which he did for 6 months. That must have been incredibly hard–to have no social life, not to talk to anyone. That’s insane. I don’t think I could have done that.

And then when you look at adult prisoners, who you might have less compassion for, you realize they are these kids. I don’t see adult prisoners the same way anymore. It’s been a huge perception shift.

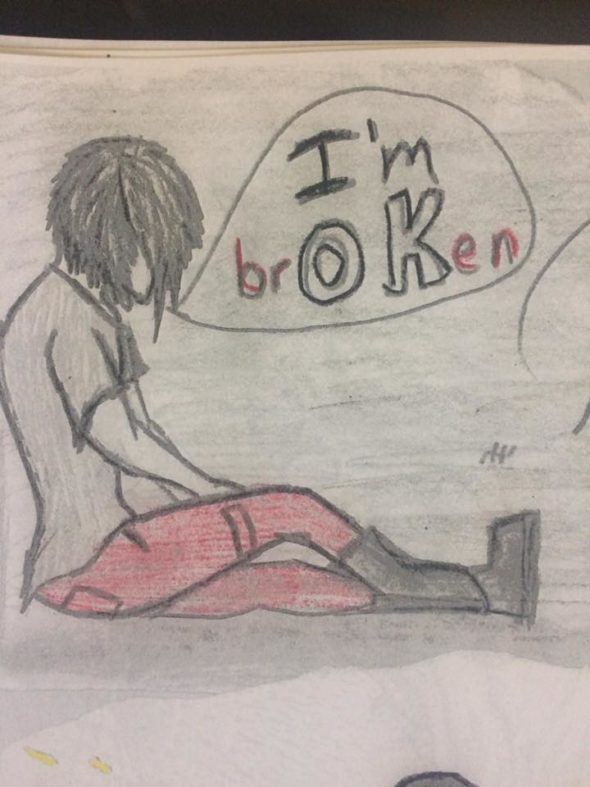

Student art from Pine Hills Youth Correctional.

Sarah: For me, Free Verse has been a learning experience about what teaching is. It’s a spiritual thing to spend time with people and not want anything from them. It’s a relationship that’s not about me. And I’ve never been thanked so much by other students, undergrads, tutoring students. My other kids–I love them, but their lives are different–most of them wouldn’t know to say those words: “Thank you for being so generous with your time.” It wouldn’t even occur to them that I have my own time.

How does funding work?

Sarah: That is an interesting and complicated story. We volunteered for 1.5 years. I had my people who I relied on but when I started getting new teachers, I realized that I couldn’t just expect the same consistency. I applied for an individual grant, with a maximum ask of $1000, and we got it. And that’s when we did a Kickstarter. We had a goal of $2000 and we got to $4000. So then we applied for another grant. I was like, I’m going to ask for more. It meant we got to go to Pine Hill Youth Correctional in Miles City.

It’s been such a rewarding experience, to figure out everything as you go. I realized I needed non-profit status–it was a long process, presentations to the board, and lots of waiting. When something is possible to do, I want to do it yesterday. Our mission aligned with the Missoula Writing Collaborative’s (MWC) mission and I’m so grateful they took us in. I wrote bylaws, I made a board. This was all from internet research–and MWC took a leap of faith. It’s been good for Free Verse and MWC.

Then I applied for grants through Humanities Montana and The Washington Foundation. I thought, “I’m gonna try to get $8000,” and then they gave it me. I just try to take advantage of every single opportunity I see. I love writing grants because I get to talk about my kids. It’s not a good party trick to talk about incarcerated kids. People walk away. Writing grants is a great chance to brag about them.

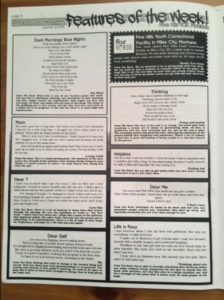

The Beat Within

Talk about your chapbook project. Does publication empower your students? What role does digital technology play in your organization (website, blog, social media etc.)?

Sarah: If they choose to submit it, we publish their work in a national journal of art and writing by incarcerated kids, The Beat Within, and in our own Free Verse chapbook. As background, we have a confidentiality agreement with the detention centers–we can never share student names. The kids want us to share their names because they’re proud of themselves but just because they want us to share it now doesn’t mean they’ll agree with their 15-year-old selves later on.

Bracha: A few months ago, when we brought in their chapbook, we had students pick out poems that they liked from the chapbook. Two students picked the same poem, made a beat, and rapped the poem for the class. Turns out the poem was written by one of the students in the room. About an hour before, this same kid, the author of the poem, had opened up to us about past suicide attempts and that he hasn’t seen a family member in over three years. Since all of the work is anonymous, no one had any idea who had written that poem. While the other kids rapped, the author tried to keep his smile in check. It was adorable to watch. He didn’t tell the other kids that they just rapped his poem, but after class he thanked us and was super excited that other kids liked his work. That was one of the most rewarding moments.

Sarah: When we brought issues of The Beat Within to Pine Hills, kids took copies and signed the poems they’d written like they were yearbooks. They asked to take copies to their cells, and then home with them when they left.

We could do better on social media. We want more people to think about this issue. Because people don’t think about it, like Bracha was saying. They just think these must be bad kids. Every time I see a comment on Facebook or our website gets views, someone saying “wow,” or “incredible” about one of our kid’s poems, it makes me so happy. Maybe one more person gets how incredible these kids are, how much they’re dealing with.

Can you tell me about your teaching experience before Free Verse? What do you enjoy about teaching?

Bracha: I taught Hebrew School on the Upper East Side in Manhattan. I taught the most entitled and wealthy kids probably in the world–it put me through college. Many of these kids had private drivers or their families had private drivers. Yet, the kids in Juvy show me more respect, which just blows my mind given what they’ve been through and the childhoods they never really had. In whatever environment, I like when I can make learning fun for kids. Especially when the interest comes from the kids and not from the teacher. I’m a strong believer in Democratic learning.

Sarah: I’ve taught undergrads, high school, and elementary kids but the skills required to work with our Free Verse students are unteachable–some people connect to these kids and some don’t. #Friere. That’s why I’m so grateful for my teachers. They’re what make this organization. I can’t be in there as much now that I serve as Program Officer for Humanities Montana. I’m an extremely controlling person. I’m just really lucky that I have people I trust enough to do this–and do it better than I ever did. My job now is to make their job possible. To fund it, to organize it, to do the marketing, communication, grant writing, meetings, etc., so they can teach. And connect with those kids. Or just entertain them.

Jules Ohman and former instructor Caylin Capra Thomas at Pine Hills.

I don’t really care if my teachers are writers or education majors. You can learn that stuff. It’s about whether they know how to talk to a child and how to listen, how to really hear them. Also, all my teachers are cool people, so the kids generally like them, and that’s pretty make-or-break. Before I met Bracha, I wasn’t sure about putting someone new in the classroom because it’s an arduous process and I’m super picky, but she’s amazing with them and an amazing teacher. It’s not about the writing background–it’s an unteachable quality, being able to understand a student, being able to pick out something meaningful from a lesson and make it meaningful to the kids, being able to be honest and comfortable while you’re teaching.

What inspires you?

Bracha: This could have been me. There is literally no difference besides the circumstance that they were born into. When I think of that I simply can’t not do something.

Sarah: Their voices are important. They are social activists, they are smart, they know more about the system than I will ever know. They are incredible and their voices are so silenced. To try to pay attention to them is our whole job. When you ask them how to reduce recidivism, they’ll say, “I need support in school.” They know what they need.

Why writing?

Sarah: I could provide stats on emotional processing, concrete and anecdotal–basically, what they won’t say out loud they will write down. I started with writing because it’s what I know, and then it seemed like they wanted to do it. We always tell them, “You can throw it out, you can keep it, or you can give it to me.” They’ll look me in the eye and say, “I want you to read this.”

And then having something to show people helps people relate to these kids and help reach our systemic goal, which is to raise awareness and secure the resources to fund our project. But we never go in wanting a product. Our work is to serve these kids. They’re not there to make things for us.

How can our readers help out?

Sarah: They can donate of course but they can also talk about this! Think about this. Look into it. These are kids, they’re not criminals. Of course, we’d love help with money so we can do our work but you can also do your work!

Bracha: Help out in any way you can. Get involved with your local detention center.

Sarah: Show up. Elect the right people. Pay attention and care about issues affecting those who are incarcerated. We could use any support that we can get. Our goal is for people to change their attitudes about this.

The Free Verse Chapbook, available here.

What ideas do you have for the future?

Bracha: I want to see more services for the kids while they are in Juvenile Detention like mental health services, recreation, art, and college prep. We also want to provide services to help them transition out. Many of the kids fall behind their school work while in the JDC and have no way of catching up once they return to school. Another huge issue is that in Montana, when a students does not show up for two weeks, the public schools can unenroll them.

Sarah: I have a million plans–connecting with judges so that they get to hear the kids’ voices and not just their public defenders. Talking to teachers who might be working with these kids once they’re released. Lobbying, talking to legislators to get funding for these facilities. Offering tutoring for them when they leave, so they have help with school work or just someone to talk to who wants them to succeed. Holding more community readings and conversations, starting more conversations. Working with other organizations that bring art and writing to young people. Connecting kids on the outside with kids inside–artistic collaboration between non-incarcerated and incarcerated kids can reduce some of that stigma and misunderstanding. Getting into halls in rural parts of the state. I just connected with a woman working in the Poplar detention center on the Fort Peck reservation in northeast Montana. We need people like her in every hall. We need it yesterday.

Let’s Pretend

This game we

Play is let’s pretend

And pretend we’re

Not pretending

Life is hard,

We all get that,

But that doesn’t

Mean we’ve hit

Rock bottom

Our past may

Let us down but

That doesn’t mean

We can’t reach

Back and grab it

And tear the bad

Memories to shreds

Your will is your power

Don’t pretend you don’t

Have it

Or you won’t

Anonymous

(Missoula County Juvenile Detention Center)

***

Note: The opinions expressed by interviewees of the Submittable blog are theirs alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Submittable.

![]()

Sarah Kahn has an MFA in Fiction and an MA in Literature from the University of Montana. She is the Program Officer at Humanities Montana, teaches for the Missoula Writing Collaborative, and tutors for Hughes Tutoring. She served as a teaching assistant and instructor for undergraduate literature and fiction courses at the University of Montana.

Bracha Tenenbaum received her BA in Philosophy from Columbia University. She has taught Hebrew and Judaic studies to grades K-5 and enjoys helping students through the writing process. She currently works as Product Manager for Submittable and spends her free time painting, trail running or playing Dominion.